Chapter II

History of the Research

Eduardo Saavedra studied Roman road XXVII of the Antonine Itinerary, in the segment running from Asturica (Astorga) to Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza), and more specifically in the part crossing the province of Soria, from Uxama (Osma) to Augustobriga (Muro) . This prompted him to conduct several excavations in 1853; as such he was the first to demonstrate scientifically the siting of Numantia on the hill of La Muela de Garray, doing so in a work laureled by the Royal Academy of History in 1861. Apart from Saavedra’s research, archaeological work continued in the city. The first official campaigns were conducted from 1861 to 1867 (the year in which the 20th Centenary of the Numantine Feat was celebrated), by a Commission of the Real Academia de la Historia.

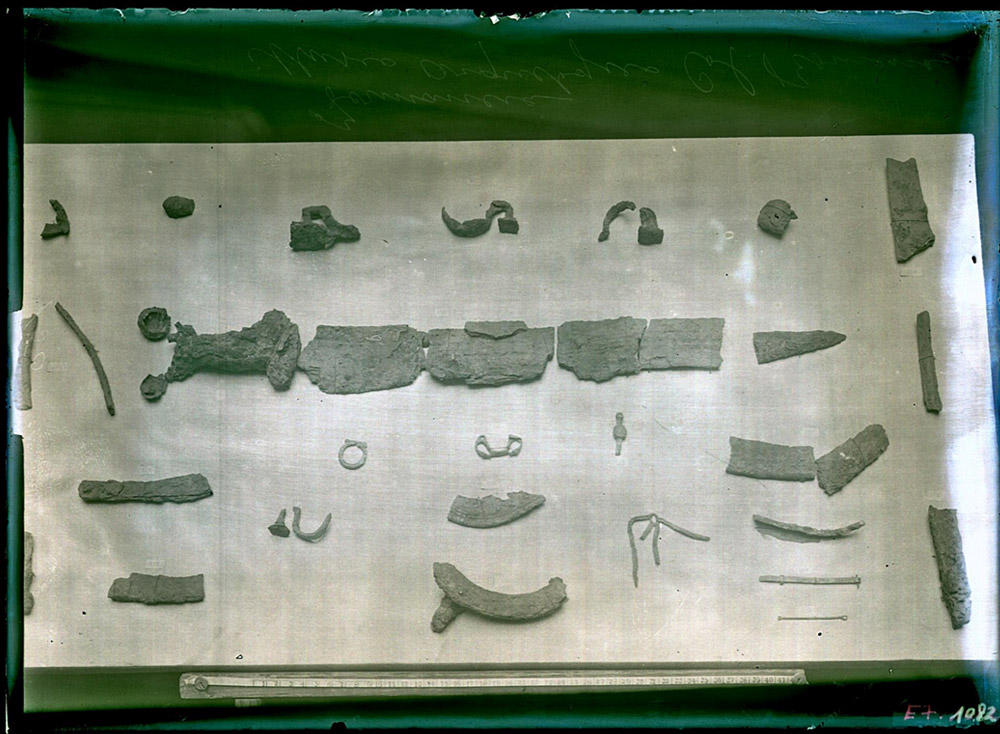

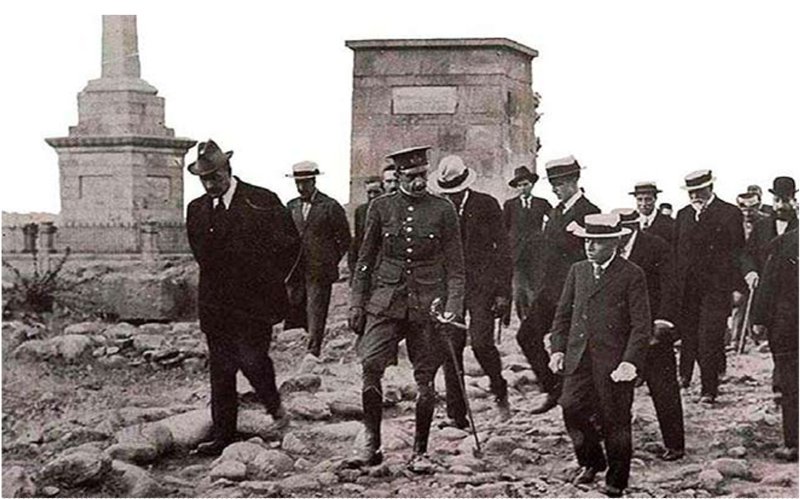

In the early twentieth century the history of Numantia drew the attention of European researchers like Adolf Schulten (helped in the archaeological work by Constantin Köenen and in the topographical work and military strategy by Lammerer) who carried out the first studies under the patronage of Kaiser Wilhelm II (as honorary colonel of the Dragoons Regiment of Numantia). He brokered excavations in the city in 1905 and, from 1906 to 1912, in the Roman Camps and the Scipio siege site. The results and reports on this work were published in the most renowned research reviews of the time, Numantia thus coming in for serious academic consideration at the start of the century.

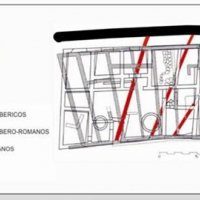

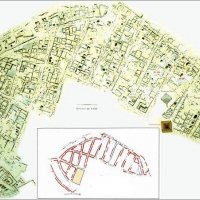

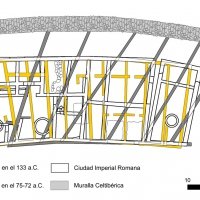

A new commission of the Real Academia de la Historia was set up (1906 to 1923), chaired by Saavedra and, as from 1912, by Mélida, the members including González Simancas, Marqués de Cerralbo, Abad Gómez Santacruz and Blas Taracena, first curator of the Numantine Museum. This work revealed a large surface area of the city (c. 6-7 hectares); the streets of stepping stones were considered to correspond to the Celtiberian city of 133 BCE, thereafter destroyed by Scipio, and another overlaid one of more regular stones to the city of the Roman era. Nowadays we know that they were in fact two phases of the same Roman city. To vouch for the antiquity of “the city” of streets with stepping stones they took their cue from the city of Carthage (3rd century BCE), but without taking into account the even earlier example of Pompeii.

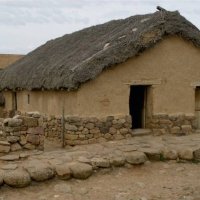

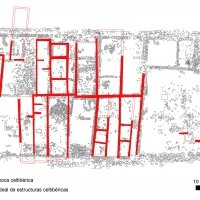

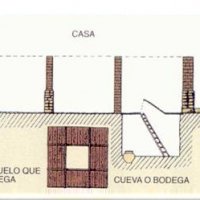

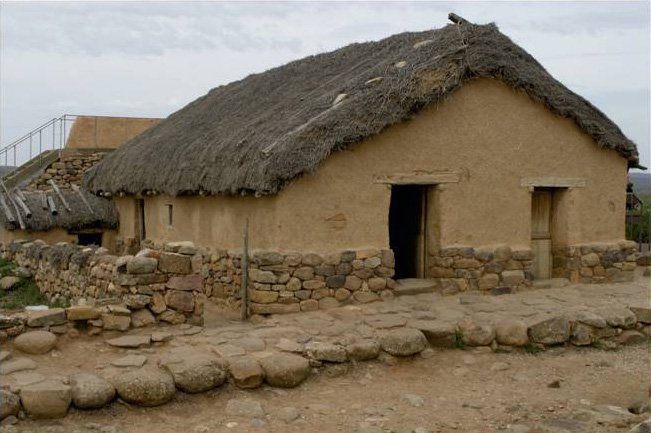

The Commission did not consider the stratigraphic work of Schulten (1945:170) and Köenen in Block IV (1905), who documented below the Roman city, next to the city wall, two superimposed Celtiberian levels, attributing the older to the city destroyed by Scipio in 133 BCE and the superimposed city to the later one brought to an end in the Sertorian Wars (75-72 BCE). The houses of the lower level, 12 metres long and about 3 metres wide, were divided into three rooms. The first one gave onto another underground room or “cellar”, 2 metres deep and serving as a larder. What Schulten overlooked is that these houses left room between their narrow back side and the city wall for a circulatory street.

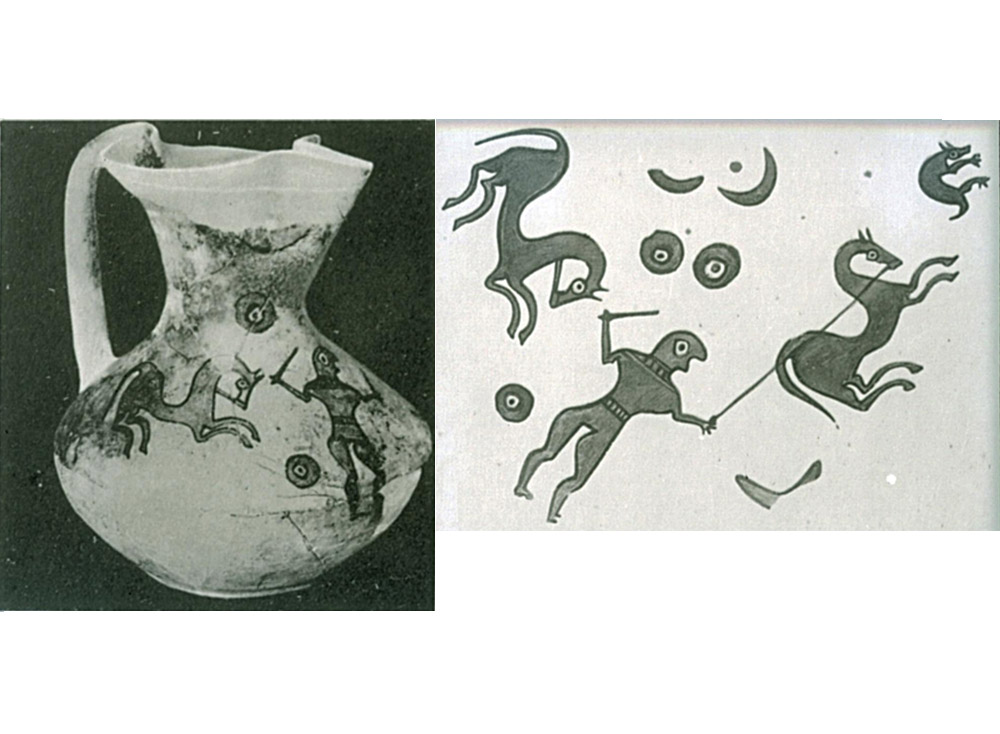

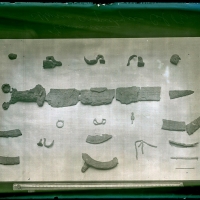

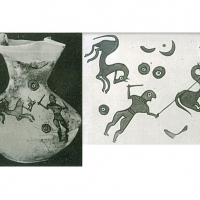

Recent studies, based on the city’s visible groundplan, on ancient plans and aerial photos, plus an excavation of block XXIII, enable us to distinguish between two Celtiberian cities. The oldest corresponds to the one destroyed by Scipio in 133 BCE. Singular Numantine ceramics, found in a store built on to one of these houses, were wrongly dated to the late 1st century BCE on mistaken assessment of their Roman influence. As for the second, Appian tells us that Scipio gave Numantia and its territory to those native tribes that had helped to conquer it; this new city then being destroyed in the Sertorian Wars (75-72 BCE).

Carbon-14 analyses of the base of the city wall in the northern zone have thrown up a date of 340±50 BCE. This gives us a yardstick for the foundation of the city, borne out by the information from the Celtiberian necropolis and information from block XXIII, which was destroyed by Scipio in 133 BCE, made up by rectangular houses compartmentalised into three rooms, organised in blocks. The city destroyed in Sertorian times (75-72 BCE) is worse for wear since it was largely swept away by the construction raised on the Imperial Roman city. Nonetheless, we have been able to document this city, showing it to be made up by longer, rectangular houses built onto the wall, in different parts of the city.

As from the work by Blas Taracena and up to the transfer of powers to the Regional Authority of Castilla y León (Junta de Castilla y León) in 1985, only sporadic Numantia work was carried out. In 1963, for example, F. Wattenberg performed a series of stratigraphic sections that gave insights into the first phases of city occupancy and produced a re-dating of the ceramic finds on the basis of this new stratigraphy. Commemoration of the 21st Centenary of the Numantine Feat in 1967 brought several Spanish Specialists to Soria. The chance was then taken to submit for their consideration the General Plan of Work in Numantia, approved by the Directorate General of Fine Arts in 1962. The plan was then trimmed down to only a few improvements.

The assumption of powers by the Junta de Castilla y León brought systematic attention back to the archaeological site, whereupon cleaning and study campaigns were carried out in favour of its conservation. In 1989-1990 a start was made on fitting out the guardhouses and the Excavations Commission. At the same time, under an agreement between the Junta de Castilla y León, The Provincial Council of Soria (Diputación de Soria) and the National Employment Institute (INEM), a guided trail was laid out with twelve stopping-off points illustrated with drawings and explanatory panels. A video was also set up in the guardhouse to give a historic explanation of the city. This latter project (1994) was the forerunner of a Master Plan of the Junta de Castilla y León, drawn up by the Numantia Archaeological Team led by Professor Alfredo Jimeno Martínez (UCM), with archaeological research as its main remit.

Gallery of chapter images

go on to chapter III >>>Numantia and its Surroundings

Bibliographical references

- Baquedano, Enrique (2017). “El descubrimiento de Numancia”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia . Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 18-29. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- Blech, Michael (2017). “La trayectoria de Schulten en la Alemania imperial”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia. Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 70-103. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- Blázquez, Jose María (1999). "Campamentos romanos en la Meseta hispana en época romana republicana", Edición digital a partir de Las guerras cántabras. Santander, pp. 67-118.

- Díaz-Andreu García, Margarita (2017). “Contextualizando a Schulten”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia . Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 30-45. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- García y Bellido, Antonio (1960). “Adolf Schulten”. Ex. Archivo Español de Arqueología, 33, Nº 101-102, pp. 22-228.

- González Simancas, Manuel (1927).Excavaciones de exploración en el cerro del castillo de Soria. Memoria descriptiva. Madrid.

- Graells i Fabregat, Raimon y Miguel F. Pérez Blasco (2017). “[...] für die Kenntnis der iberischen Altertümer”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia. Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 252-269. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- Gómez Gonzalo, Maria Paz e Ignasi Garcés i Estalló (2017). “Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numancia, ni héroe ni villano”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia. Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 120-137. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- Gómez Santacruz, Santiago (1914). El solar numantino: refutación de las conclusiones históricas y arqueológicas defendidas por Adolf Schulten como resultado de las excavaciones que practicó en Numancia y sus inmediaciones. Madrid.

- Gómez-Barrera, Juan Antonio (2017). “Por tierras del Duero. Soria, Adolfo Schulten y la arqueología numantina”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia. Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 46-69. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- Hofmann, Harald, y Schulten Adolf (1922). Panorama von Numantia, in 12 blättern. Dibujado por H. Hofmann, con textos de Adolf Schulten. Múnich.

- Jimeno Martínez, Alfredo (1993). “Numancia”. Departamento de Prehistoria, Universidad Complutense, II, pp. 119-134.

- Jimeno Martínez, Alfredo (2000). “Numancia: Pasado vivido, Pasado sentido”, Trabajos de Prehistoria, 57, II, pp. 175-193. ISSN: 0082-5638.

- Jimeno Martínez, Alfredo (2007). “Historia de Numancia.” Reseña de Historia de Numancia, de Adolf Schulten, en ArqueoWeb, IX, 1. ISSN-e 1139-9201.

- Jimeno Martínez, Alfredo y Antonio Chaín Galán (2005). “El plan General de trabajos en Numancia de 1962 y los problemas estratigráficos”, Kalathos: Revista del seminario de Arqueología y Etnología turolense, 24-25, (2005-2006), pp. 239-258. ISSN: 0211-5840.

- Jimeno Martínez, Alfredo y José Ignacio de la Torre Echávarri (2005). Numancia. Símbolo e historia. Madrid. ISBN: 9788446009344.

- Jimeno Martínez, Alfredo, Alberto Sanz Aragonés, Juan Pedro Benito Batanero y José Ignacio de la Torre (2004). “Numancia: conocimiento y difusión del pasado”. En Jesús del Val Recio y Consuelo Escribano (coord.): Puesta en valor del Patrimonio Arqueológico en Castilla y León. Salamanca, pp. 247-264. ISBN: 84-9718-239-1.

- Jimeno Martínez, Alfredo, Antonio Chaín Galán, Sergio Quintero, Raquel Liceras y Angel Santos (2012). “Interpretación estratigráfica de Numancia y ordenación cronológica de sus cerámicas”. Complutum, 23, I, pp. 203-218. ISSN: 1131-6993.

- Luik, Martin (2017). “La metodología de las excavaciones de Adolf Schulten”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia. Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 138-163. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- Morillo Cerdán, Ángel, Fernando Morales Hernández y Rosalía-María Durán Cabello (2017). “Schulten y los campamentos romanos republicanos en Hispania: una mirada desde el siglo XXI”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia. Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 174-201. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

- Mélida, José Ramón (1908). Excavaciones de Numancia. Madrid.

- Mélida, José Ramón (1918). Excavaciones de Numancia: Memoria de los trabajos realizados en 1916 y 1917 presenta el presidente de la comisión ejecutiva de dichas excavaciones. Madrid.

- Mélida, José Ramón (1922). Excursión a Numancia pasando por Soria y repasando la historia y las antigüedades numantinas. Madrid.

- Mélida, José Ramón y Blas Taracena Aguirre (1920). Excavaciones de Numancia: Memoria acerca de las practicadas en 1919-1920: con un apéndice en que se da cuenta de la inauguración del Museo Numantino. Madrid.

- Mélida, José Ramón, Manuel Aníbal Álvarez, Santiago Gómez Santa Cruz y Blas Taracena Aguirre (1924). "Ruinas de Numancia. Memoria descriptiva redactada conforme al plano que acompaña a las mismas". Memorias de la Junta Superior de Excavaciones y Antiguedades, 61, Madrid.

- Revilla Andía, María Luisa, Ricardo Berzosa del Campo, Juan Pablo Martínez Naranjo, José Ignacio de la Torre y Alfredo Jimeno Martínez (2005). “Numancia”, Revista de Soria, 49, pp. 39-46.

- Saavedra, Eduardo (1864). Descripción de la Via Romana entre Uxama y Augustobriga. Madrid.

- Schulten, Adolf (1905). Numantia, Eine topographisch-historische Untetsuchung. Berlín.

- Schulten, Adolf (1914). Mis excavaciones en Numancia (1905-1912). Barcelona.

- Schulten, Adolf (1931). Numantia. Die Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen, 1905-1912. Por A. Schulten, con la participación de W. Barthel, H. Dragendorff (y otros), etc. (con placas). Volumen II: Die Stadt Numantia. Múnich.

- Schulten, Adolf (1937). “Las Guerras de 154-72 A. de J.C.” Fontes Hispaniae Antiquae, IV, pp. 122-141.

- Schulten, Adolf (1945). Historia de Numancia. Barcelona.

- Seeling, Hans (1984). Konstantin Könen (1854-1929). Leben und Werk eines Archäologen. Neuss. ISBN: 3980129411.

- Taracena Aguirre, Blas (1924). Cerámica Ibérica de Numancia. Madrid.

- Torre Echávarri, José Ignacio de la (1998). “Numancia: usos y abusos de la tradición historiográfica”, Complutum, IX, pp. 193-212. ISSN: 1131-6993.

- Wattenberg García, Eloísa (2008). “Federico Wattenberg Sampere.” Estudios del Patrimonio Cultural, I, pp. 15–18. ISSN-e 1988-8015.

- Wattenberg Sampere, Federico (1963). “Las cerámicas indígenas de Numancia”. Bibliotheca Praehistorica Hispana, IV. Madrid.

- Wattenberg Sampere, Federico (1983). Excavaciones en Numancia: campaña 1963. Valladolid. ISBN 84-500-9331-7

- Wulff Alonso, Fernando (2017). “Ascendía por la colina un joven investigador alemán. A propósito de Schulten”. En: Baquedano, Enrique y Marian Arlegui Sánchez (coord.). Schulten y el descubrimiento de Numantia. Catálogo de la exposición del Museo Arqueológico Regional de Alcalá de Henares, de abril a julio de 2017 y del Museo Numantino en Soria, de julio de 2017 a enero de 2018, pp. 104-119. ISBN: 978-84-451-3607-2.

Documents

- Informe sobre las excavaciones practicadas por Eduardo Saavedra en Numancia. Ante la decisión tomada por la recién creada Sociedad Arqueológica Numismática de continuar con los trabajos, se solicita al Gobierno la concesión de una subvención económica que permita llevarlas a cabo bajo la inspección de la Real Academia de la Historia.

- 22 de julio de 1861. Minuta de oficio en la que se solicita licencia para que Eduardo Saavedra, miembro de la Comisión encargada de inspeccionar las excavaciones de Numancia, se traslade a Garray para participar en las mismas.

- 10 de abril de 1896. Carpetilla de expediente sobre el informe de Eduardo Saavedra acerca de la comunicación elevada por la Comisión de Monumentos de Soria, para la declaración de utilidad pública de los terrenos ocupados por las excavaciones de Numancia.